View Current Newsletter -

Search The Archive

Sign Up - Print

Issue

295

Article

450

Published:

8/1/2023

Adverse Possession of Fee Underlying an Easement

Chris Burti, Vice President and Senior Legal Counsel

This opinion of a divided panel of the North Carolina Court of Appeals results from a summary judgment order "settling a property dispute between disgruntled neighbors" and determining the interests of the parties in an old easement. The trial court's order granted one neighbor's trespass claim and dismissed the other neighbor's counterclaims for adverse possession and nuisance. This opinion explains the Court of Appeals' holding that the adverse possession counterclaim was improperly dismissed, its reversal of the trial court's summary judgment order, and its remand to the trial court for further proceedings.

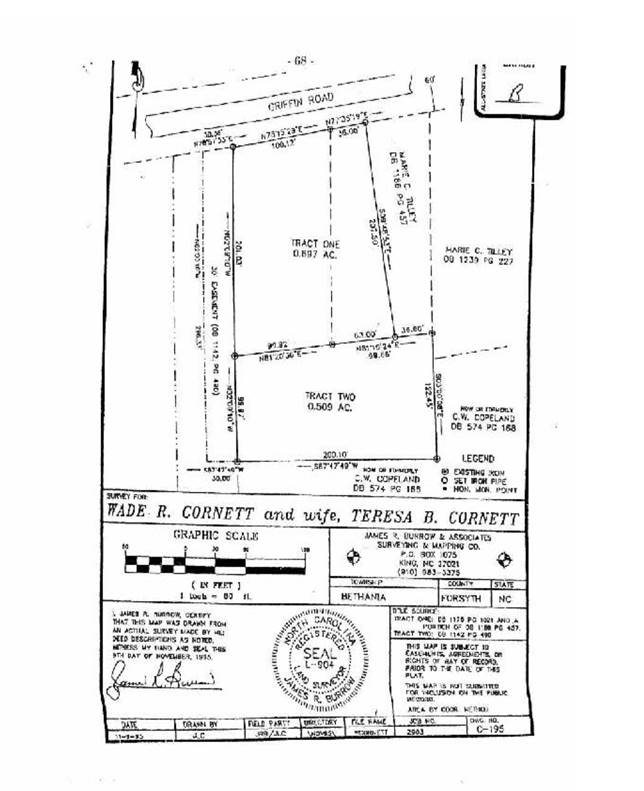

The Defendants rented a home in 1983 and bought the property in 1995. The entire property is an aggregation of several tracts of land which the seller acquired at different times. The residence is located on Tract 1 shown on the diagram copied below from the opinion. Tract 2 is the defendants' backyard behind Tract 1 to its south. Tract 1 abuts the public road on the north, and a driveway extends from the road along both tracts' western border. The Defendants have an appurtenant easement in the driveway. Adjoining Tract 2 on the south lies a larger property the owners of which reportedly maintained a cordial relationship with the defendants. In 2019 these neighbors sold this larger, southern property to the Plaintiffs and relations between the parties "quickly soured".

The Plaintiffs obtained a survey, claimed that the Defendants were encroaching on their property along the driveway and demanded removal of the encroachments. The survey showed that the Plaintiffs owned the land containing the driveway running along the western sides of Tracts 1 and 2 as well as a strip of land several feet wide running along the eastern side of the driveway and into what a casual observer might mistake for the Defendants' land. The opinion states:

Allegedly oblivious to this easement and believing that they owned the disputed corridor, the Defendants had used the driveway to access both Tracts 1 and 2 of their property, paved and maintained the driveway, and allowed guests and others to park on the driveway. On a strip of land adjacent to the driveway, [between the easement and Tracts 1 and 2] the Defendants maintained gardens, fences, a brick column, and several trees.

Also, two carports extended from the home on Tract 1 to the driveway, thus extending into the adjacent strip of land in the corridor easement. These two carports and the other structures existed on the land prior to 2000. The brick column predated the Defendants' ownership of the property. The Defendants began planting trees and a garden in 1983. They added another carport and a fence in 1991 and 1992 respectively.

Another carport was added in 1996. Since 1999, the Defendants further maintained another garden, crepe myrtle trees, and a fence. The Defendants refused to remove these alleged encroachments The Plaintiffs built a fence, with a gate, along the boundary between the driveway and Tract 1 and subsequently filed suit against the Defendants.

The Plaintiffs' complaint alleged trespass, the Defendants' counterclaim pleaded that by adverse possession, they had obtained title of the disputed corridor easement barring the Plaintiffs' trespass claim, and claimed that the new fence constituted a tortious nuisance. Both parties moved for summary judgment. The Plaintiffs requested an injunction for the removal of the alleged encroachments and the Defendants asked the trial court to grant them title to the strip of land in the corridor easement between the driveway and the Defendants' property and contested the Plaintiffs' construction of a "nuisance fence."

The trial court granted the Plaintiffs' motion and dismissed the Defendants' counterclaims and the order states:

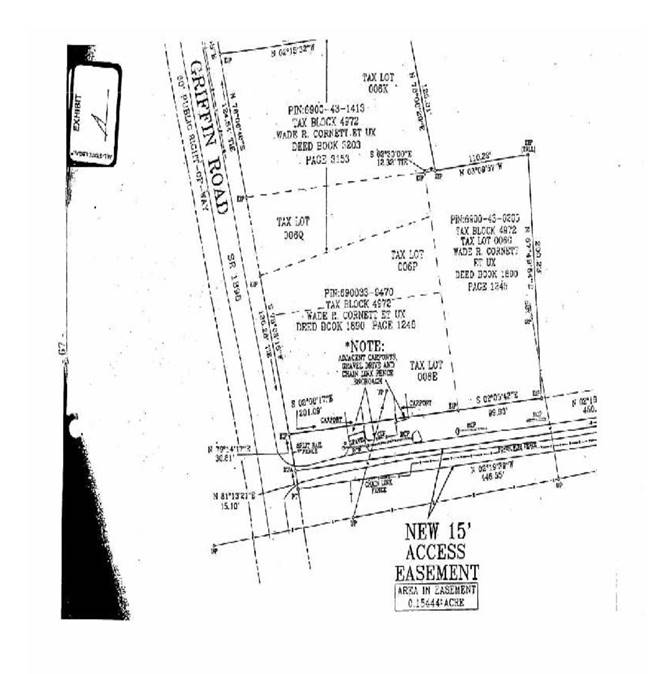

[S]ummary judgment is granted in favor of plaintiffs against defendants on all claims asserted by the plaintiffs and that defendants counterclaims are dismissed with prejudice and that defendants are further ordered to remove all structures, within 15 days of the date of this order, that are encroaching on Plaintiffs' property including the portion of Plaintiffs two carports that are located on Plaintiffs property, the split rail fence, the lion statue, chain link fence and post, a brick column and the concrete base to the smaller carport. Attached hereto as Exhibit A is a survey that shows the encroachments and Exhibit B which shows tracts 1 and 2 of Defendants property. It is further ordered that the recorded easement as set out in Book 1890 Pages 1245-1247 of the Forsyth County Register of Deed [sic] is on land owned by the Plaintiffs and the easement only applies to tract 2 as set out in Book 1890 page 1247 and shown on Exhibit B. Thus, the Defendants may only use the 30-foot recorded easement to access tract 2. Defendants may not use the recorded easement to access tract 1 which includes but is not limited to accessing their current carports. In addition, Defendants cannot use the area in the recorded easement to park vehicles on or to allow third parties to park vehicles or delivery vehicles on. In addition, Defendants may not drive on or otherwise use the paved driveway to the West of their property which is outside the 30-foot recorded easement. Defendants may use the portion of the paved driveway that is contained within the 30-foot recorded easement but only to access tract 2 of their property. Finally, the fence as built by the Plaintiffs along the eastern boundary of the 30-foot easement is legal under North Carolina law and may remain and that the cost of this action be taxed against the Defendants.

The two survey exhibits attached to the order and set out in the Court of Appeals opinion follow:

The Defendants argued that the trial court erred:

- in determining that the Defendants may not utilize the easement to access their Tract 1,

- failed to consider the presence of a prescriptive easement,

- improperly ruled on the adverse possession issue where material facts were contested,

- ordered the Defendants to remove items alleged to have trespassed on the Plaintiffs' land,

- allowed the Plaintiffs to establish a nuisance fence.

The court determined from the title history in the record that the original easement was appurtenant and only benefited Tact two. The analysis follows well established doctrine and need not be discussed in depth here. The opinion, on this issue, states:

All evidence suggested that the easement allowed for access to Tract 2 and that the Plaintiffs' use of the easement to access Tract 1 constituted a "misuse or overburdening" of the easement. City of Charlotte v. BMJ of Charlotte, LLC, 196 N.C. App. 1, 20, 675 S.E.2d 59, 71 (2009). We therefore affirm the trial court's order as to the access easement for Tract 2 but not for Tract 1, which has frontage and direct access...

The Defendants were also not successful with their appellate argument that the trial court erred by failing to consider whether they had obtained a prescriptive easement over the disputed land, losing on the procedural technicality that they did not argue this theory to the trial court. The opinion observes that they, instead, presented a counterclaim for adverse possession and while the proof necessary to establish adverse possession and a prescriptive easement claims are much the same, the Court stated that "they are nonetheless distinct actions requiring distinct pleadings. We therefore cannot consider this argument on appeal. See N.C. R. App. P. 10(a)(1); Weil v. Herring, 207 N.C. 6, 10, 175 S.E. 836, 838 (1934) ("[T]he law does not permit parties to swap horses between courts in order to get a better mount" on appeal.)."

The opinion asserts that the Defendants made it clear that they only claimed to adversely possess "the strip of land consisting of their garden, brick pillar, several trees, fencing, and portions of their carports. The Defendants [did] not allege adverse possession of the shared driveway, which they used with ... permission and acknowledge is contained within the easement." The driveway, and this disputed strip of land rests within the easement. The Defendants contested the trial court's dismissal of this claim because they maintained this strip of land for over twenty years and they argued that they alleged all elements necessary to support a claim of adverse possession.

The Court devotes a considerable portion of the opinion to the issue of adverse possession as claimed by the Defendants. The opinion begins its analysis by setting out the basic tenets of North Carolina's doctrine of adverse possession.

Adverse possession "is not favored in the law." Potts v. Burnette, 301 N.C. 663, 667, 273 S.E.2d 285, 288 (1981). The possessor's use of the land, therefore, "is presumed to be permissive." Id. at 666, 273 S.E.2d at 288.

A successful claim of adverse possession requires that the possession be "open, continuous, exclusive, actual and notorious" ("OCEAN") for the prescribed period. Jones v. Miles, 189 N.C. App. 289, 299, 658 S.E.2d 23, 30 (2008). Our Supreme Court has more eloquently described these requirements as follows:

It consists in actual possession, with an intent to hold solely for the possessor to the exclusion of others, and is denoted by the exercise of acts of dominion over the land, in making the ordinary use and taking the ordinary profits of which it is susceptible in its present state, such acts to be so repeated as to show that they are done in the character of owner, in opposition to right or claim of any other person, and not merely as an occasional trespasser.

It must be decided and notorious as the nature of the land will permit, affording unequivocal indication to all persons that he is exercising thereon the dominion of owner. Locklear v. Savage, 159 N.C. 236, 237, 74 S.E. 347, 348 (1912). The prescriptive period for adverse possession, without color of title, is 20 years. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 1-40 (2022).

No action for the recovery or possession of real property, or the issues and profits thereof, shall be maintained when the person in possession thereof, or defendant in the action, or those under whom he claims, has possessed the property under known and visible lines and boundaries adversely to all other persons for 20 years; and such possession so held gives a title in fee to the possessor, in such property, against all persons not under disability. Id.

One may assert a claim of adverse possession upon a portion of a tract of land so long as such portion is identifiable by "known and visible lines and boundaries." Dockery v. Hocutt, 357 N.C. 210, 218, 581 S.E.2d 431, 436 (2003). However, "his claim is limited to the area(s) actually possessed, and the burden is upon the claimant to establish his title to the land in that manner." Id.

A goodly amount of this analysis then considers whether the owner of an easement in North Carolina can adversely possess underlying servient fee simple. The Court stated that it was unable to locate North Carolina authority definitively answering this question. the opinion notes that North Carolina precedent allows the owner of land burdened with an easement to claim adverse possession and to extinguish the dominant easement on his own property citing; Skvarla v. Park, 62 N.C. App. 482, 488, 303 S.E.2d 354, 358 (1983). In this case under appeal, the alleged adverse possessor is the owner of the dominant easement and a successful action for adverse possession in this case would not only extinguish the easement and would divest the servient estate owner of title.

Proof of adverse possession of an easement is challenging. Much like a tenancy in common the adverse user has a right to be there so the evidence of use beyond that right has to be a bit extreme. As to a tenancy in common, proof of ouster is required. Here the Court of Appeals states:

The principal concern with adversely possessing the land of one's own easement lies in the adverseness-or hostility-of the possession. This hostility element requires "a use of such nature and exercised under such circumstances as to manifest and give notice that the use is being made under claim of right." Dulin v. Faires, 266 N.C. 257, 261, 145 S.E.2d 873, 875 (1966). "[T]his does not mean that ill will or animosity must exist between the respective claimants. It only means that the one in possession of the land claims the exclusive right thereto." Brewer v. Brewer, 238 N.C. 607, 611, 78 S.E.2d 719, 722 (1953). Regardless of the "length of time in the enjoyment of his easement," an easement owner cannot divest the servient owner of his land merely because he made some use of the land consistent with the easement. Everett v. Dockery, 52 N.C. (7 Jones) 390, 392 (1860). However, where the dominant estate owner's use of the easement is so inconsistent with its permissive use as to inhibit the rights of the servient estate owner, it follows that the possession is hostile. We therefore hold that, where the elements of adverse possession are otherwise satisfied, the owner of a dominant tenement may adversely possess the land underlying his own easement.

Note: it is clear that the evidence of "hostile" use of an easement to support an adverse possession claim must be so excessive so as to put the owner on notice of adverse claim and this will always be a question of fact.

The Court also touched upon the issue of whether a party may adversely possess land mistakenly believed to be owned during the entire prescriptive period.

Our Supreme Court has answered this question in the affirmative. A party may succeed in an adverse possession claim "though the claim of title is founded on a mistake." Walls v. Grohman, 315 N.C. 239, 249, 337 S.E.2d 556, 562 (1985). Since 1985, this state has been among a majority of states which allow a claim for adverse possession though the adverse possessor be oblivious to the adverse nature of his possession. Id.

The majority opinion's analysis of whether the Defendants appropriately alleged an adverse possession claim sufficient to overcome a motion to dismiss is illuminating and worth reading in preparation of either pleading or defending an adverse possession claim. However, we shall move on to the Courts analysis of the issue of trespass in the interest of brevity. Suffice it to say that the Court of Appeals determined that "although the disputed strip of land is within an easement, the easement was for ingress and egress, not for the building of permanent structures", that the Defendants had presented evidence sufficient to overcome the Plaintiffs' motion to dismiss, and the trial court erred in granting summary judgment for the Plaintiffs.

Because the Court held that the trial court erred in dismissing the Defendants' adverse possession counterclaim, it necessarily ruled that the trial court also erred in granting the Plaintiffs' motion for summary judgment on their trespass claim.

... adverse possession is a defense to trespass. In Williams v. South & South Rentals, the plaintiff sought to require the removal of an apartment building which encroached approximately one square foot onto the plaintiff's property. This Court in Williams said, "While the action sounds in trespass because there is no dispute over title or location of the boundary line, plaintiff seeks a permanent remedy and is subject to the twenty-year statute of limitations for adverse possession." 82 N.C. App. 378, 382, 346 S.E.2d 665, 667 (1986). ...Thus, if the Defendants are successful in showing adverse possession of the disputed strip of land for twenty years, it would defeat the Plaintiffs' claim of trespass and request to remove the encroachments.

The Defendants alleged that the Plaintiffs erected a nuisance fence between the driveway and the Defendants' property. The opinion states that it is not clear whether the fence would be on the Defendants' or the Plaintiffs' property presuming the Defendants' succeed in their adverse possession counterclaim. The courts' comments are brief:

If the fence is on the Plaintiffs' property, its mere presence on the easement is not an actionable issue so long as its presence does not interfere with the Defendants' permissive use of the easement. "The owners of the servient estate may make any use of their property and road not inconsistent with the reasonable use and enjoyment of the easement granted." Shingleton v. State, 260 N.C. 451, 457, 133 S.E.2d 183, 187 (1963); cf. Ingraham v. Hough, 46 N.C. (1 Jones) 39, 44 (1853) (holding that an impassable gate across a right of way is an "interruption[] to the user of the easement"). The Defendants allege that the fence frustrates their use of the easement in that it does not allow them access to Tract 1 of their property or, rather, makes it more difficult to access Tract 1. Because we hold that the easement does not grant access to Tract 1 and because the Defendants did not otherwise argue that the fence impedes their access to Tract 2, the Defendants and their land are uninjured. Therefore, this argument is overruled. Yet, because the issue of whether the fence is on the Defendants' property or the Plaintiffs' property is unresolved, this issue must be remanded to the trial court.

Judge Murphy concurred in the result only without separate opinion. Judge Tyson concurred in part in the result and dissented in part and authored a separate opinion. Judge Tyson opined that the plurality's opinion properly affirms the trial court's prohibition of the Defendants from using the driveway easement to access Tract 1 of their property, but thought it proper to affirm the trial court's dismissal of the Defendants' counterclaim and of Plaintiffs' motion for summary judgment on their trespass claims. Simply stated, Judge Tyson misapplied the law to the facts and deemed the evidence of hostile use by the Defendants insufficient to overcome the presumption of permissive use as a matter of law even when viewed in the light most favorable to the Defendants.

This case is a cautionary tale for closing attorneys. When a survey discloses encroachments and the seller reports that there has never been a problem, this case makes it clear that new ownership can become a problem and that the matters need to be resolved prior to closing while the parties are still amicable. The case also shows why obtaining a survey prior to closing is prudent.

- Home

- ALTA Best Practices

- TRID

- Register of Deeds

- Calculator

- Forms

- Priors

- Commercial

- Newsletters

- What Is Title Insurance?

- News

- Your ?'s

- About Us

- Contact Us

- History

- Rates

- Ratings

- Our Creed

- En Español

- Privacy

Resources

Statewide Title, Inc. is a member of ALTA®, the NCLTA and the FEA.