View Current Newsletter -

Search The Archive

Sign Up - Print

Unsubscribe

Issue 255

Published: 7/1/2019

COA Analyzes Right to Erect Gates on Platted Easement

Chris Burti, Vice President and Senior Legal Counsel

It is not uncommon for the issue of when a servient owner may exercise the right to erect gates across an easement to arise. However while the common law makes it clear that there is a right to do so when reasonably necessary, there is not a lot of appellate guidance as to what specifically should be considered reasonable. This case adds to the body of law informing us as to when the right arises.

The plaintiffs in this appeal brought the action seeking a declaration and other relief concerning an easement extending across their burdened property to the defendants' property. The parties own rural adjacent tracts of land and the defendants access a nearby State road over easements across the plaintiffs 'land. The plaintiffs built two gates and fencing along these private roads to fence in their horses that do not prevent the defendants from accessing the public road, as they have provided the defendants with the access code for the gates. The defendants however, contend that based on language in the chain of title concerning the easements, Plaintiffs are not permitted to construct the gates on the easement and the plaintiffs commenced this action seeking an order declaring their right to construct and maintain the gates in question. The trial judge ordered summary judgment in favor of the defendant's counterclaim seeking a declaration that the plaintiffs have no right to erect and maintain the gates and directing them to remove the gates. The plaintiffs appealed the trial court's order granting summary judgment to the defendants. After review, the Court of Appeals reversed and remanded the case to the trial court for further proceedings.

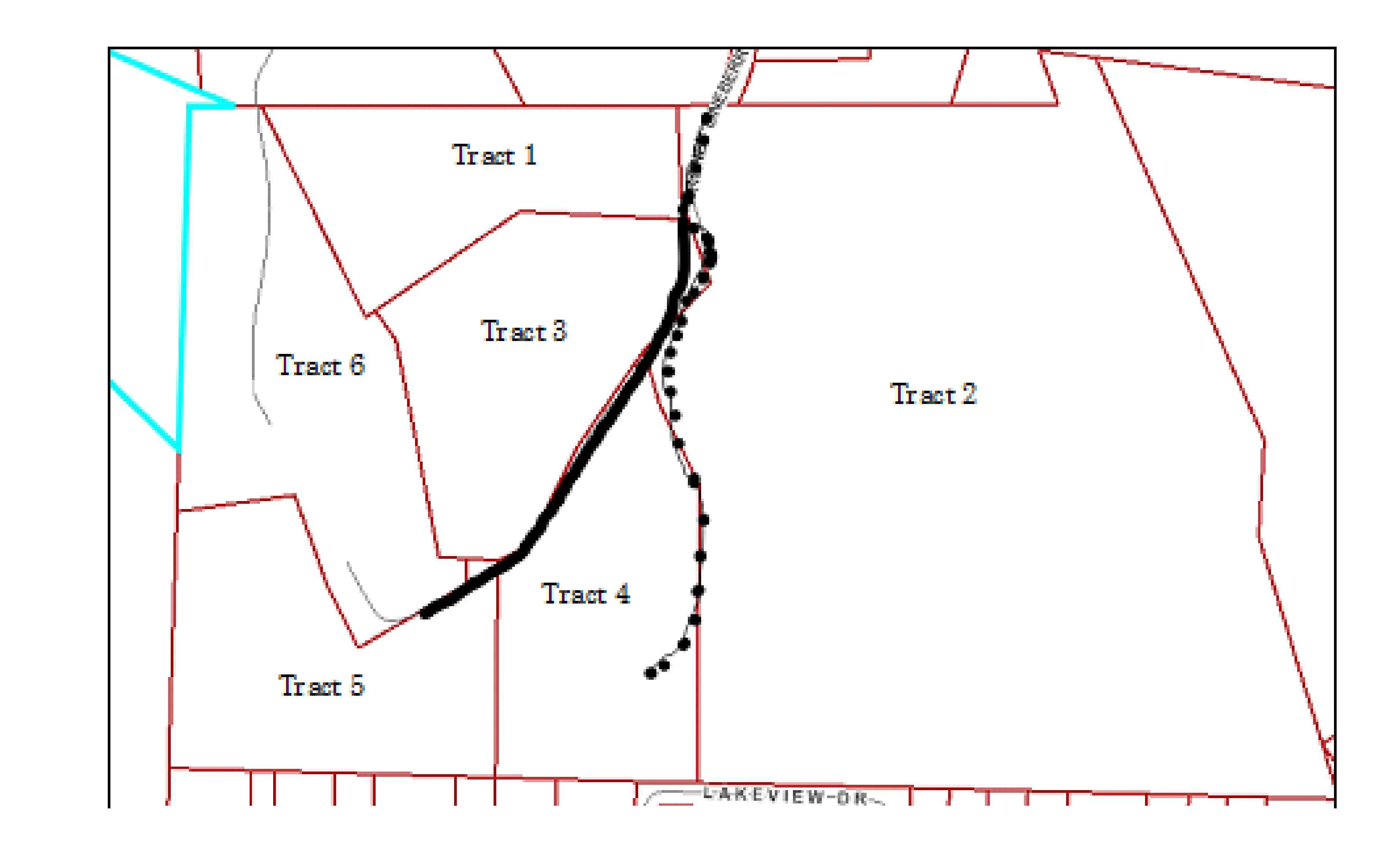

The map below was included in the opinion for clarity in describing the chain of title at issue and is included here likewise. The map shows six tracts of land, referred in the opinion as Tracts 1-6, and the plaintiffs own Tracts 1 and 3 while the defendants own Tract 4 and only these three tracts are relevant to the opinion. The defendants access Roney Lineberry Road (public) by way of the two private roads shown in their approximate location.

Until 1989, all tracts were part of a single tract of over 100 acres. Subsequently, it was subdivided into six tracts using four maps with the two easement roads having been created to provide access to the several tracts as they were being created. In 1989, the owner at the time recorded a map (the "1989 Map") that divided the large tract into two separate tracts; one of approximately 66 acres, now Tracts 1 and 2, and another tract of approximately 43 acres which became Tracts 3-6. The filing of the 1989 Map created an easement (the "1989 Easement") shown as the dotted-line road meandering at or near the border dividing the two tracts to provide more than one access point to each of the two large tracts. Significantly, the 1989 Map asserts that the easement shown is to remain "open for egress and regress" for the benefit of the owner of the 66 and 43 acre tracts created by the division as follows:

Note: The existing private road shall remain open for egress and regress to [the sixty-six (66) acre and forty-three (43) acre tracts formed by the 1989 Map]. Road shall be maintained by the "owner" or "owners" of [the two tracts].

In 1996, the owner of the 66 acre tract filed a map (the "1996 Map") subdividing that tract into two tracts, depicted above as the 9 acre Tract 1 and the 57 acre Tract 2. The 1996 Map shows the 1989 Easement in essentially the same location as on the 1989 Map, restating that the easement is to remain open for the benefit of the adjacent 43 acre tract as well as the newly formed Tracts 1 and 2.

In 2000, the owner of the 43 acre tract filed a further subdivision map (the "2000 Map") dividing that tract into three tracts, shown above as Tract 3, 4, and a tract that subsequently became 5 and 6 above. The 2000 Map shows part of the 1989 Easement plus a new private road shown in the above map as the solid line (the "2000 Easement"), to provide access from the 1989 Easement to the three newly formed tracts. This easement is described on the 2000 Map as a "30' R/W [right-of-way] EASEMENT" however, it does not contain any other language indicating that the 2000 Easement is to remain "open" as was the case in the 1989 Easement.

The plaintiffs subsequently erected two access gates to keep their horses secured on their tracts, but the opinion emphasizes that there is nothing in the record to indicate whether the gates were installed on the 1989 Easement or the 2000 Easement, as some portion of both easements are on the plaintiffs' land. The plaintiffs provided the defendants with the access code to the electronic locks on the gates so that they could still access the public road over the easements and a number of disputes subsequently arose between the parties concerning the gates.

The trial court entered summary judgment declaring that plaintiffs were prohibited "from having gates, bars, fences and the like on the Private Road" and directing them to "remove the gates erected upon the Private Road[.]"

The opinion asserts the general rule in North Carolina that:

...the owner of a servient estate "may erect gates across [an easement] when necessary to the reasonable enjoyment of his estate, provided they are not of such nature as to materially impair or unreasonably interfere" with the purpose of the easement to the dominant estate. Chesson v. Jordan, 224 N.C. 289, 293, 29 S.E.2d 906, 909 (1944); accord Merrell v. Jenkins, 242 N.C. 636, 637-38, 89 S.E.2d 242, 243-44 (1955). However, our Supreme Court has held that the owner of a servient estate generally may not erect gates on an easement where the instrument granting the easement provides that the easement is to remain "open," stating as follows:Generally, the grant of a way without reservation of the right to maintain gates does not necessarily preclude the owner of the land from having them; unless it is expressly stipulated that the way shall be an open one or it appears from the terms of the grant or the circumstances that such was the intention, the owner of the servient estate may erect gates across the way if they are constructed so as not to interfere unreasonably with the right of passage.Setzer v. Annas, 286 N.C. 534, 539, 212 S.E.2d 154, 157 (1975) (emphasis added). Indeed, our Supreme Court has interpreted express language suggesting that an easement remain "open" to mean that it must be free of obstructions, such as fences or gates. See Patton v. W. Carolina Educ. Co., 101 N.C. 408, 409-11, 8 S.E. 140, 141-42 (1888) (holding that "[a]street, with gates or fences across it, is not what was reserved" by a deed stating "that the street now opened up through to the college land...shall be kept open" (emphasis added)).

The Court notes that the 2000 Map contains no language requiring the easement to remain open, but does explicitly refer to the 1989 Easement. The opinion observes that the trial court in granting the defendants' summary judgment motion, determined that they were entitled to have the private road remain open and required the plaintiffs to remove the gates. While not ruling completely in favor of the plaintiffs, the Court of Appeals determined the defendants were not entitled to summary judgment because there was nothing on the 2000 Map or other documents in the chain of title which required the 2000 Easement had to be kept "open." Therefore, the Court of Appeals concluded that the plaintiffs:

"may erect gates across [the 2000 Easement] when necessary to the reasonable enjoyment of [their] estate, provided they are not of such nature as to materially impair or unreasonably interfere" with the purpose of the easement to Defendants' tract. Chesson, 224 N.C. at 293, 29 S.E.2dat 909; see Runyon v. Paley, 331 N.C. 293, 305, 416 S.E.2d 177, 186 (1992) (holding that the meaning of unambiguous language contained in an easement is a question of law). Whether the gates, if erected on the 2000 Easement, would actually materially impair or unreasonably interfere with Defendants' right of egress and ingress is not an issue before us.

We conclude further that Plaintiffs are, nonetheless, bound by the language contained in the 1989 Map with respect to the private road constituting the 1989 Easement: Plaintiffs must keep this easement "open." See Setzer, 286 N.C. at 539, 212 S.E.2d at 157. As such, we conclude that Plaintiffs are not allowed to install gates along the 1989 Easement. We further conclude that Defendants, as the owners of Tract 4, have the right to enforce this restriction.

The Court noted that part of the 2000 Easement is also part of the 1989 Easement and as to that portion, the plaintiffs are bound by the requirement to keep it "open". The lack of clarity in the record as to the exact location of the respective easements and the location of the gates on those easements led the Court to remand the case to the trial court for further proceeding to determine the facts and rule thereon.

It should be considered illuminating that when dealing with restricting livestock or residential security, as to the reasonableness question of the gates themselves, the appellate courts seem to have little trouble. See: Happ v. Creek Pointe Homeowner's Ass'n, 717 S.E.2d 401 (N.C. App., 2011).

- Home

- ALTA Best Practices

- TRID

- Register of Deeds

- Calculator

- Forms

- Priors

- Commercial

- Newsletters

- What Is Title Insurance?

- News

- Your ?'s

- About Us

- Contact Us

- History

- Rates

- Ratings

- Our Creed

- En Español

- Privacy

Resources

Statewide Title, Inc. is a member of ALTA®, the NCLTA and the FEA.