View Current Newsletter -

Search The Archive

Sign Up - Print

Unsubscribe

Issue 266

Published: 10/1/2020

Chris Burti, Vice President and Senior Legal Counsel

The Petitioner in this proceeding appealed from an order denying her claim to an elective share of the estate of her late husband ("Decedent"). The Petitioner contended that she never signed an express waiver of her right to her elective share and that a waiver cannot be properly implied from the terms of the separation agreement that she and her deceased husband executed. The Court of Appeals did not agree and affirmed the trial court's order.

The facts as reported in the opinion disclose that the Petitioner and Decedent separated in 2014 and the Petitioner subsequently sought post-separation support, alimony, equitable distribution, and attorney's fees from the trial court. After court ordered mediation, the parties executed a Mediated Settlement Agreement and Consent Judgment ("MSA"), which was entered by the trial court.

With regard to this MSA, the Court of Appeals opinion states:

The parties stipulated that the MSA memorialized their agreement. The trial court found that the parties had "agreed to resolve all pending issues"; the MSA was "calculated to finally resolve their financial claims against one another"; and that "[t]he parties waive[d] further findings of fact." The MSA ordered Decedent to deed certain real property to Petitioner in exchange for Petitioner's assumption and payment of all debts associated with the property. It also provided that Petitioner and Decedent would have as their "sole and separate property all household furniture and other personal property" at the time in their possession. Additionally, each party "acknowledge[d] sole ownership in the other" of certain personal belongings owned prior to the marriage, inherited during the marriage, or given or loaned to the party by a relative. Petitioner and Decedent each received a vehicle as "sole and separate property." Each party would be responsible for the debts associated with the assets distributed to him or her and for the debts in his or her individual name. Petitioner and Decedent retained bank accounts in their respective names as "sole and separate property," and identified retirement accounts and joint bank accounts were distributed to either Petitioner or Decedent. The MSA specified that the parties had divided all intangible property such as stocks and bonds to their satisfaction, and provided that "neither party shall make any claim against the other for any intangible personal property in the name, possession or control of the other."

... At the conclusion of the MSA, the parties agreed that it "contains the entire understanding of the parties, and there are no representations, warranties, covenants, or undertakings other than those expressly set forth herein."

At the time of Decedent's death, he and the Petitioner were still married but remained separated. His Will, naming his son as executor of the estate, devised his entire estate to his two children and was admitted to probate. The Will provided, in part:

As of the execution of this Will, I am physically separated from my spouse, Pennaritta Cherry Cracker. She and I have executed a Mediated Settlement Agreement and Consent Judgment on marital property that contains a complete and total waiver of alimony which includes a waiver of any claim for post separation support, alimony and attorney's fees associated with any claims that were raised in our separation. In addition, both Pennaritta C. Cracker and myself have executed a Release of Estate and Inheritance Rights, a copy of which is attached as Exhibit A and incorporated herein by reference to this Will. No release was attached to the Will

The Petitioner filed a timely claim for an elective share of to which the executor objected claiming it was barred because the Petitioner had waived her elective share right in the terms of the MSA. The clerk determined that the duly executed MSA waived Petitioner's right to claim any interest in Decedent's property after death, denied Petitioner's claim for an elective share and the Petitioner timely appealed this order to the superior court which affirmed the clerk's order.

The Petitioner argues in her appeal that she is entitled to an elective share of the Decedent's estate because she did not explicitly waive this entitlement in a signed writing as required by the statute. The opinion observes that the "statutory right 'may be waived, wholly or partially, before or after marriage, with or without consideration, by a written waiver signed by the surviving spouse . . . .' N.C. Gen. Stat. § 30-3.6(a) (2019)." As for applying this requirement to the facts at hand the Court states:

"The statutory law of this state permits a married couple to execute a separation agreement 'not inconsistent with public policy which shall be legal, valid, and binding in all respects.'" Sedberry v. Johnson, 62 N.C. App. 425, 429, 302 S.E.2d 924, 927 (1983) (quoting N.C. Gen. Stat. § 52-10.1). Such agreements are construed according to "the same rules which govern the interpretation of contracts generally." Lane v. Scarborough, 284 N.C. 407, 409, 200 S.E.2d 622, 624 (1973). As with contracts more broadly, in interpreting a marital agreement, "the primary purpose is to ascertain the intention of the parties at the moment of its execution." Id. at 409-10, 200 S.E.2d at 624. A contract "encompasses not only its express provisions but also all such implied provisions as are necessary to effect the intention of the parties unless express terms prevent such inclusion." Id. at 410, 200 S.E.2d at 624-25 (citing 4 Williston, Contracts § 601B (3d ed. 1961)). "The court will be prepared to imply a term if there arises from the language of the contract itself, and the circumstances under which it is entered into, an inference that the parties must have intended [the] stipulation in question." Id. at 410, 200 S.E.2d at 624-25 (quoting 1 Chitty, Contracts § 693 (23d ed. A.G. Guest 1968)).

Guided by Lane and Sharpe, the Court concludes that; " 'the specific terms of the [MSA] are totally inconsistent with an intention that the parties would each retain the right to share in the estate of the other . . . if he or she were to become the surviving spouse.'" ... " '[T]he intention of each party to release his or her share in the estate of the other is implicit in the express provisions of their separation agreement, their situation[,] and purpose at the time the instrument was executed.' Lane, 284 N.C. at 412, 200 S.E.2d at 625. 'The law will, therefore, imply the release and specifically enforce it.' Id. at 412, 200 S.E.2d at 625. We hold that Petitioner released her right to share in Decedent's estate by the execution of the MSA. '

This case along with Lane and Sharpe, should make it easier for real property practitioners to rely on separation agreements that use broad release language without including more specific references inchoate rights such as provided by N.C.G.S. Section 29-30 and N.C.G.S. Section 30-3.1 that we would prefer to see included.

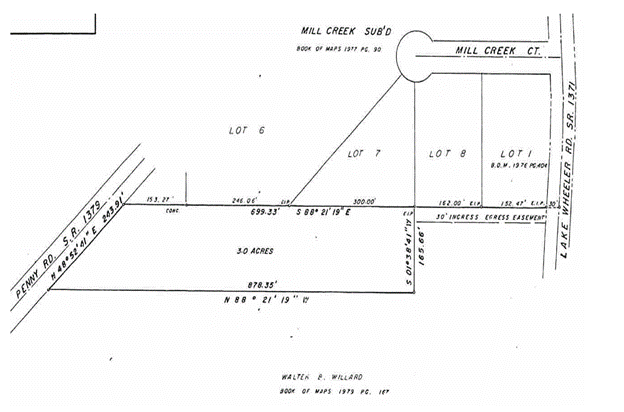

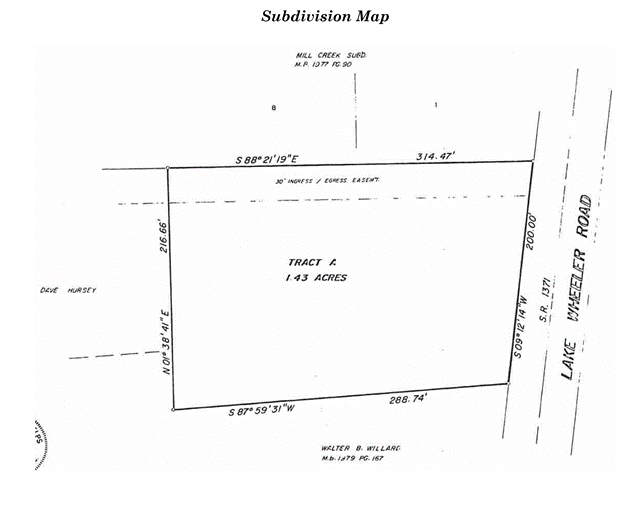

This appeal was from a trial court judgment on the pleadings where a thirty-foot wide easement was depicted on plats in the parties' respective chains of title that were referenced in the original deeds from the common owner. A significant part of the opinion discusses procedural issues raised in the appeal which we will not discuss further. The two plats used to convey the property in the respective chains of title used by the common grantor and referenced in the original deeds were included in the opinion and shown below.

The first plat shows the three acre parcel first conveyed by reference to the plat and depicts a "30' INGRESS EGRESS EASEMENT"

The second plat shows the 1.43 acre tract of the defendants and it also depicts the easement.

The defendants contended that there was a question of facts because:

1. there was no express grant or reservation of the easement in either chain of title,

2. the purported easement was depicted by a dotted line and not surveyed,

3. the description was ambiguous because the designation of 30' wasn't clear as to whether it referred to distance or width.

Citing Tanglewood Prop. Owners' Ass'n, Inc. v. Isenhour, 254 N.C. App. 823, 830, 803 S.E.2d 453, 458 (2017) the opinion, (ellipsis and citation omitted), relates that when an appurtenant easement is created for the purpose of benefiting particular land, it attaches to, passes with, and is an incident of ownership of that land. It may be created in several ways, including grant, estoppel, way of necessity, implication, dedication, prescription, reservation, and condemnation.

Though easements generally must be created in writing, courts will find the existence of an easement implied by plat as the doctrine is recognized in North Carolina. An appurtenant easement may be created by implied dedication formally or informally and may be created when the purchaser is conveyed the land by a description that relies on a plat where the land is sold in reference to it, the plat depicts the easement with sufficient information to adequately describe it and court expresses the doctrine that an express grant is not required.

As to the adequacy of the description of the easement depicted by these plats:

"Both recorded maps show that easement across Defendants' property: (a) is labeled as an ingress/egress easement; (b) is coterminous with the northern boundary of Defendants' property, which is described in metes and bounds in the Barbour Jr. Deed, on the Subdivision Map, and on the Penny Rd. Property Map, and is labeled 314.47 feet long; (c) intersects with Lake Wheeler Road on its east side; (d) intersects with the Penny Rd. Property on the west side; and (e) is 30 feet wide, as can be inferred from the "30' ingress/egress easement" label."

The defendants further argued that it is not possible to determine if the easement is 30 feet wide since the easement's label on the Subdivision Map does not contain the word "wide" and that the southern boundary line of the easement is not capable of being located "because it is represented by a dotted line, which indicates that this boundary was not surveyed." The court summarily disposed of the issues by stating:

"...according to the Subdivision Map, the length of the easement is 314.47 feet. Hence, the 30-foot descriptor refers to the width of the easement...The northern boundary of the easement is coterminous with the northern boundary of the Lake Wheeler Rd. Property. The southern boundary of the easement is located 30 feet from and below the northern boundary of the property at all points along the easement."

This opinion is useful to title examiners because it makes it clear that in North Carolina the doctrine is well established that when a plat depicts an easement benefitting property over the grantor's remaining, the plat is then used to convey that property and using all reasonable inferences from the information on that plat, it adequately describes the easement, the use creates an appurtenant easement for the grantee. As it is in the chain of title of any successor in interest of the grantor, it burdens that successors land even where, as here, the map is not used in the successor's grant. See Reed v. Elmore, 246 N.C. 221 (1957).

- Home

- ALTA Best Practices

- TRID

- Register of Deeds

- Calculator

- Forms

- Priors

- Commercial

- Newsletters

- What Is Title Insurance?

- News

- Your ?'s

- About Us

- Contact Us

- History

- Rates

- Ratings

- Our Creed

- En Español

- Privacy

Resources

Statewide Title, Inc. is a member of ALTA®, the NCLTA and the FEA.